Posted9 Feb 2015

- In

Guest blog by Oscar Co-Librettist John Cox - Part 2

Truth, Art and Life

Oscar’s nemesis took the beautiful form of Lord Alfred Douglas, the young man he fell in love with – according to Oscar the love of his life, crowding out his real but less consuming love for his wife and two sons. Douglas, known to all London as Bosie, was the youngest son of the Marquess of Queensberry, whose eldest son and heir had committed suicide, probably as a result of his father’s fury over his intimate relationship with the Prime Minister, Earl Rosebery. (You couldn’t make this up!)

Queensberry was notoriously violent and combative. (He gave his name to the rules of boxing, which are still in use today.) He was certain that Bosie’s relationship with Oscar was also physical, and did everything in his power to break it up. Oscar was not the kind to be intimidated, and Bosie hated his father with such a passion that he constantly goaded Oscar into confrontation with him. Eventually Queensberry accused Oscar in writing of posing as a sodomite – in other words, “prove that you aren’t.” (The penalty for sodomy was life imprisonment.) Bosie blindly pushed Oscar into the trap set by his father. Wilde sued for libel, lost, and was himself arrested on the strength of the evidence produced in justification byQueensberry. It is tempting to speculate that Queensberry issued an ultimatum to the government to “take down Oscar Wilde and I will spare Rosebery.” There is much circumstantial evidence to support this: in fact, Rosebery attempted to resign the morning afterQueensberry left his visiting card bearing the historic insult at Wilde’s club. However, he was persuaded by the cabinet to reconsider and stayed in office until one month after Wilde was convicted.

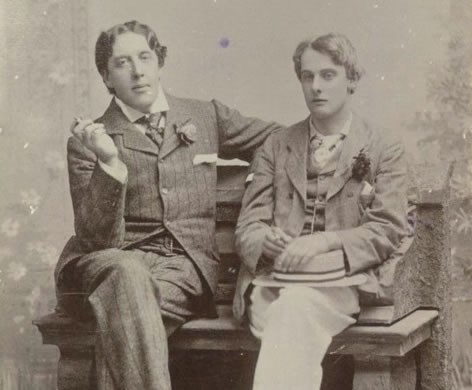

Reed Luplau as Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas. Photo by Kelly & Massa. And, photo of Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas.

Traditionally, a tragic hero must make fateful choices that enable the nemesis to do its work. Wilde certainly resembled Othello who “loved not wisely but too well,” or Macbeth, who allowed a “consort” to lead him into a fatal course of action. He even resembled Faust in submitting to the will of a serial tempter. In the end, his tragedy played out publicly on a stage of his own choosing and, fittingly for Oscar, had much to do with style. He was able to present a conventional self-portrait of a happy, well established family man within an ever-widening social circle of famous people. Yet he chose to pursue, equally publicly, a double life (he called it “feasting with panthers”) with total disregard for appearances. He seemed always confident that he was invulnerable, that he could “get away with it.” Even when on trial, he entertained the court endlessly with his quick-witted ripostes to the prosecution. He defined celebrity for the modern era. His tragic flaw was pride, which prevented him from seeing himself as anything other than a winner. But against Queensberry he lost, and his fame turned to infamy overnight.

Wilde’s reputation as a writer has recovered triumphantly in the century since his death, while his example as a warrior for sexual tolerance has achieved heroic status. The opera passes over the miserable limbo between his release from prison and his release from life, except in gratefully setting to music parts of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, his sole masterpiece from this period and one of the greatest narrative poems in the English language. We simply close by leaving it to his old friend Walt Whitman to welcome him to his place amongst the immortals of world literature, where he will always be. Meanwhile we, the beneficiaries of his genius and his pain, must never forget that a hero makes choices, and that it was Oscar Wilde’s choice alone to stand and answer his accusers. Time recedes, taking with it the reckoning of much that was unworthy, while leaving intact the recognition of his deep humanity and his unique understanding of the relationship between truth, art, and life.

John Cox is the co-librettist of Oscar and one of the world’s foremost opera directors.

Comments are closed.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More