Posted6 Feb 2015

- In

Guest blog by Oscar Co-Librettist John Cox - Part 1

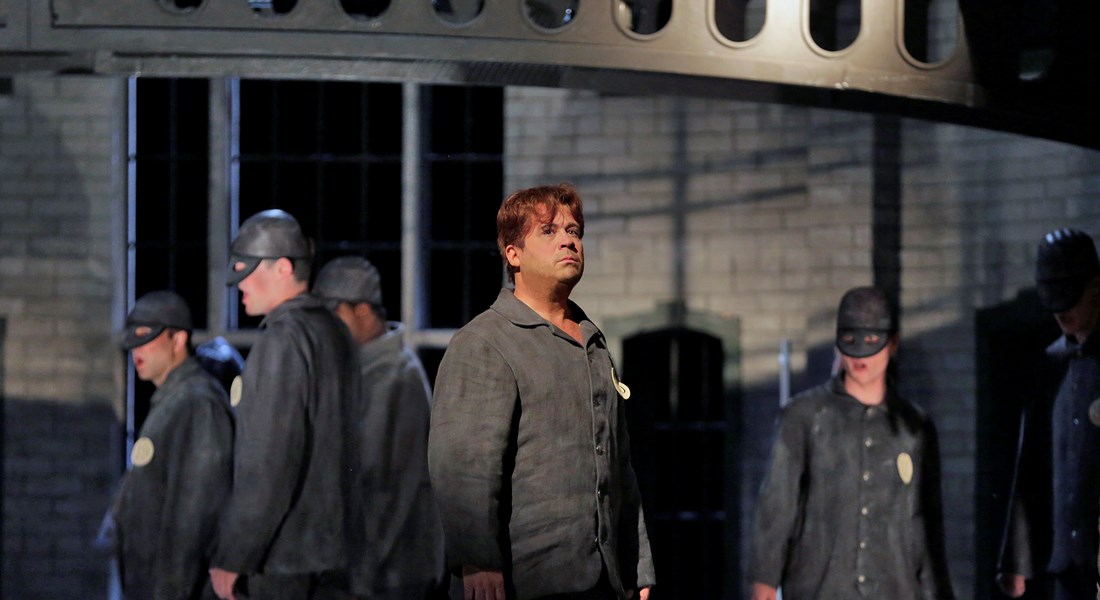

The common perception of Oscar Wilde is as a great writer and notorious homosexual. We wish in our opera to accept this duality and modulate it into a perception of him as a tragic hero. The greatness required to qualify for such an upgrade is evident in his brilliant career. As playwright, novelist, poet, journalist, wit, and public personality, he was at least the equal of any contemporary. What we offer here is testimony, suitably inflected for the theater, of the events that turned his comedy to tragedy, plunging him into a purgatory of social humiliation and physical suffering through imprisonment with hard labor, thence to discard him as a spent husk. His resurgence from victim to hero came only posthumously.

The small group of friends who welcomed him back to freedom hustled him off to France before society was aware of his release. Oscar Wilde lived on for a few short years, never to recover his career, his money, his place in society, his wife, his children – or, in the end, even the key relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, which was the cause of his downfall. He never set foot in Britain again, wandering, like Oedipus, destitute and dependent until death took him at the age of 46. Only then would the world tolerate his rehabilitation and turn his infamy back into fame.

There was a political side to his story. First, Oscar was Irish at a time when the tide of Irish nationalism was gathering strength and home rule becoming one of the bitterest and most divisive issues in the history of British politics. He was in sympathy with his homeland; Lady Wilde, his mother, was a fearless propagandist for the cause of independence. Another issue of lower profile but growing concern was the increasing incidence in society of male homosexuality, frequently involving married men, which eventually provoked parliamentary action. The Criminal Law Amendment Act, signed into law by Queen Victoria in 1885, was originally drafted to protect underage girls from sexual exploitation; however, thanks to a late additional provision, it outlawed “acts of gross indecency” between men.

Oscar was a victim of this law. For all his passionate invocation of the classical Greek ideal as found in the dialogues of Plato, he could not escape a tangle of sexual commerce with working-class youths who readily took the witness stand against him – the man who had just delivered to the London theater the finest comedy in English for a hundred years. It is hard to understand why the state bore down so mercilessly upon the author of The Importance of Being Earnest, a genius who both artistically and socially was its brightest star; why the government’s law officers demanded so rapidly both the trial and the retrial; why the Home Secretary refused every petition for remission of his barbaric jail sentence. Here Oscar’s story moves to another level of classical literature, that of tragedy, in which the gods always prescribe a nemesis to the protagonist in order to engineer his downfall.

To be continued...

Comments are closed.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More