Posted12 Sep 2016

- In

Watching Turandot with Modern Eyes

Turandot is often called a fantasy fable, a fictitious legend that serves as a cautionary tale about love and leadership. Composer Giacomo Puccini based his opera on a Persian short story and a commedia dell’arte play of the same name. The opera depicts the cruelty of a princess and the toll her citizens pay. The moral is that true love can transform even the hardest of hearts and overcome brutality.

However, the story elements demand a deeper examination from today’s viewer.

Puccini composed Turandot in 1924, at a time when no one had internet and few Westerners traveled to China. In 2016, it is imperative that one views Turandot with the understanding that Puccini's imagined China is entirely fictitious, a setting meant to distance his story from the geographical and political landscape of Italy. Puccini wrote at a time when Europeans exoticized China and based their ideas of Asian culture on cultural appropriations and stereotype.

China unofficially banned any performance of Turandot until the 1998 production in the Forbidden City of Beijing. The story itself is an appropriation of several cultures having passed through the lens of various retellings: a French version of a Persian story transformed into a commedia dell’arte play that inspired an opera suddenly set in an imagined China. In experiencing this opera, one then must relinquish the idea of cultural authenticity, but still hope for a production that offers respectful cultural representation.

The characters of Ping, Pong, and Pang can at first glance seem buffoonish and possibly offensive. However, in Puccini’s day, these characters may have seemed familiar. Commedia dell’arte is a classic style of Italian theatre that uses clowning, extreme gesture, masks, and ensemble movement. It was a popular theatrical form of Italian theater that also used archetypal clowns to present narratives and ideas to the masses. Commedia clowns included a hero and his lover; the zanni or mischievous servants; a rogue, Punch who’s usually disfigured; and a vechhio or wise old man, amongst others. These are a handful of examples from the commedia dell’arte archetypal tropes. While Turandot is an epic, romantic drama, the influences of commedia dell’arte remain. Ping, Pong, and Pang seem to represent the trio of vecchi, the older sages.

In the commedia dell’arte tradition, the vecchi are often of the merchant or elitist class. The vecchi characters also present an opposition to the love story. In Turandot, the characters of Ping, Pong, and Pang are then clearly the vechhi who try desperately to thwart Calaf’s pursuit of the Princess Turandot. They criticize the bloodshed created by the cruel princess’ treatment of her suitors. They lament their time away from their private homes and families caused by their civil responsibilities. They warn Calaf of his destructive love interest. So Ping, Pong, and Pang are Chinese characters portrayed through the construct of a theatrical form with which Puccini was already familiar.

Another story element that begs examination is the treatment of both female characters, Turandot and Liù. The Princess Turandot refuses to marry and executes her suitors as epic revenge for an ancestor’s rape. The servant girl Liù withstands physical torture to protect the identity of Calaf because she has loved him her whole life. These are two women with incredibly strong willpower. However, Liù does not garner Calaf’s affection and she kills herself. In the final act, the Princess Turandot succumbs to Calaf’s aggressive pursuit and marries him, relieving her kingdom of years of bloodshed.

This storyline is, of course, not unique to opera. But in 2016, such a resolution for these female characters may elicit a different response from that of an audience member from ninety years ago. Perhaps that is what keeps this art relevant. Appreciating opera doesn’t mean forgiving the form its flaws. Many classic operas were composed by European men over a hundred years ago.

Puccini died before he wrote the ending of this opera. Who knows how he would have truly resolved his story? In recent years, various productions of Turandot have imagined a more gentle transformation of the Princess, showing a clearer love story evolving between Calaf and Turandot.

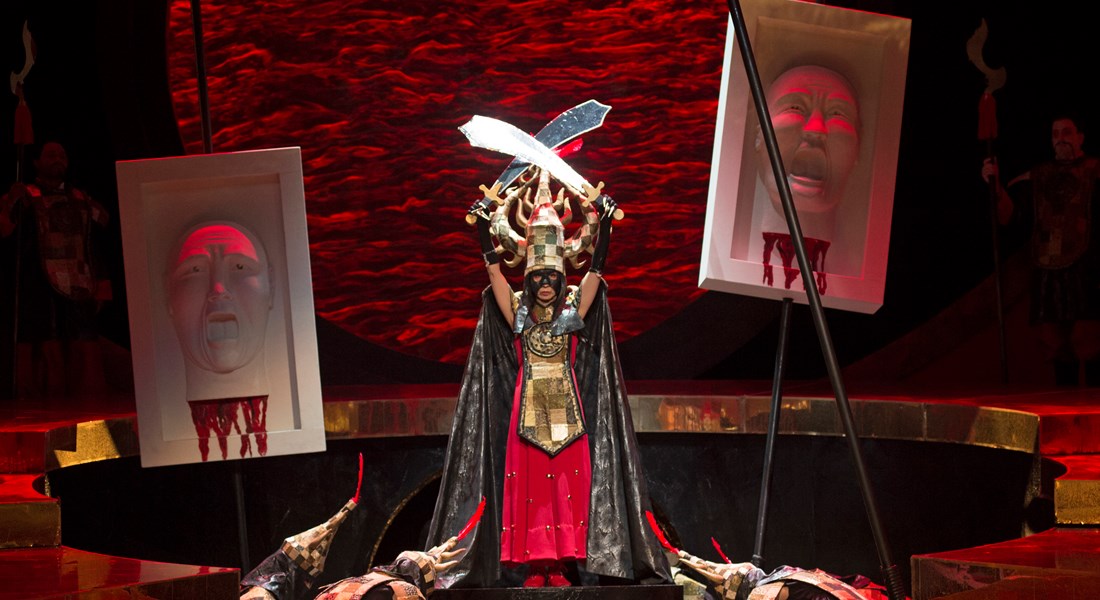

The opera possesses sumptuous sets, ornate costumes, and memorable music. Who doesn't immediately recognize Calaf's third act aria "Nessun dorma"? The sheer power of Turandot’s voice, the unified harmonies of Ping, Pang, and Pong, and the agile high notes of Liù’s two arias stand up to the test of time.

Globalization and gender roles have changed the way we interpret stories and art. In 2016, Turandot might resonate differently with modern audiences and offer new lessons, ideas, and opportunities for discourse. Perhaps the power of this piece resides not only in its epic grandeur and music, but in its potential to begin a conversation about cultural and gender awareness in the art of opera.

Leave your comment below.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More