Posted26 Sep 2019

- In

Fruit Salad: The Mosaic Modernism of The Love for Three Oranges

It is more than surprising that Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, long a staple in European opera houses, has been largely neglected in the United States. Not only did Prokofiev compose the work in America after fleeing the Russian Revolution, but Three Oranges occupies a special status as the first opera by a foreign composer to be commissioned by an American company. The whirlwind path to its 1921 Chicago premiere became the subject of widespread fascination, and the first performances made a tremendous splash, delighting audiences and shocking critics.

Furthermore, Three Oranges as a mosaic of cultural influences mirrors the American Project, as operas like George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935) and Kurt Weill’s Street Scene (1946) would later explore. In fact, when asked of what nationality the opera was, Prokofiev aptly described it as “written in French on an Italian subject by a Russian composer for an American theatre.” More broadly, it is this eclectic spirit, reflected in Prokofiev’s storytelling and music, which makes The Love for Three Oranges a profoundly modern breakthrough in the history of opera.

An amalgamation of traditional Italian fairy tales, the convoluted story of a hypochondriac prince’s quest for three oranges was concocted by 18th century Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi, who triumphantly mocked the emerging realist theatre movement by proving that pure silliness still won the day. Russian playwright Vsevolod Meyerhold, who gave his adaptation to Prokofiev as a possible subject for an opera before the composer departed for America, added to the madness with fourth-wall-breaking “spectators” who react to the action on stage.

Prokofiev, however, went a step further, seizing upon these spectators to emphasize the mixed-bag nature of the drama. Before the "real" opera even begins, diehard fans of four different kinds of theatre – tragedy, comedy, romance, and farce – storm the stage to demand their preferred genre. Their battle is broken up by a fifth group, the Eccentrics, who introduce the tale and simply insist it be seen through to its end. But as the opera progresses, the different factions of this captive audience get excited about different moments: the dark conspiracy to overthrow the Prince, Truffaldino's hilarious party plans, the Prince's nonsensical orange obsession, the passionate romance of the Prince and Princess. Ultimately, despite the comedic veil of parody and pantomime cast over the entire opera, the spectators' reactions reveal that Three Oranges is truly unclassifiable.

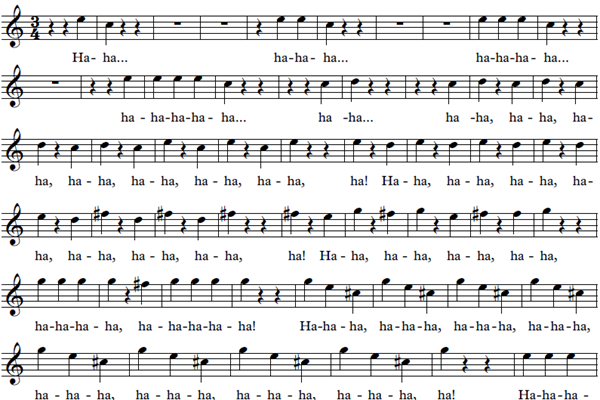

Yet this multifaceted character would barely translate if not for Prokofiev’s extraordinarily vivid score. The wide-ranging musical commentary, while often sparsely orchestrated for the clarity of the text, breathes life into the unpredictable twists in the drama. For the comedy fans, Prokofiev’s inventive musical jokes are sure to entertain, ranging from a curtain-raising “trumpeter” honking out a crass fanfare on a bass trombone, to the Prince’s “singing” of groans, shivers, and, most memorably, an overwhelming fit of laughter. On the other hand, the wicked plot against the crown is reinforced by the underworld’s menacing, Beethovenian “fate” motif, building to Fata Morgana’s truly terrifying, ritualistic curse. And in perhaps the most drastic shift of the opera, the emerging love between the Prince and Princess Ninetta is accompanied by a shockingly delicate, gorgeous, and almost impressionistic canopy of sound.

Such stylistic range, though perhaps taken to new heights in this opera, is hardly unusual for Prokofiev, whose music is timeless precisely because it captures everything we feel. Nevertheless, it gives new meaning to the onstage audience. As a trailblazing modernist composer, Prokofiev was deeply frustrated by critics’ attempts to pigeonhole his musical language – for example, by demanding of him a more consistent, conventional lyricism. For Three Oranges, he cunningly pre-empted such attacks, as well as the inevitable backlash to writing an absurd, comedy-filled opera in a time of worldwide upheaval, by mirroring his critics in the single-minded histrionics of the spectators.

An added bonus of this surreal stylistic hybrid is that it allows directors to continue revitalizing Three Oranges with their own interpretations. Alessandro Talevi’s production for Festival O19 brings the opera’s kaleidoscopic essence full circle by connecting the Prince’s quest with Prokofiev’s personal journey from Europe to the United States. Colliding Gozzi’s commedia dell’arte characters with figures and themes of Prokofiev’s time, Talevi calls to mind the opera’s cross-cultural origins, within a broader narrative reflecting Europe’s post-WWI turn to America as a land of opportunity and rebirth.

The Prince's obsession may not be so random after all. Oranges are themselves a hybrid creation bred to stay fresh for long periods of time. Little surprise, then, that the eclectic drama and music of The Love for Three Oranges make the opera feel fresh 100 years on – and, in the context of Opera Philadelphia’s Festival O19, highlight why opera continues to matter in the 21st century.

Leo Sarbanes is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in music.

This story appears in the O19 Festival Book.

Photos and Credits:

1. Prokofiev during his years in America. Credit: Library of Congress

2. Left: In Act II, the Prince "sings" a laugh like never before. Right: As Fata Morgana and the traitors escape, the low brass blasts out the underworld "fate" motif.

Leave your comment below.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More