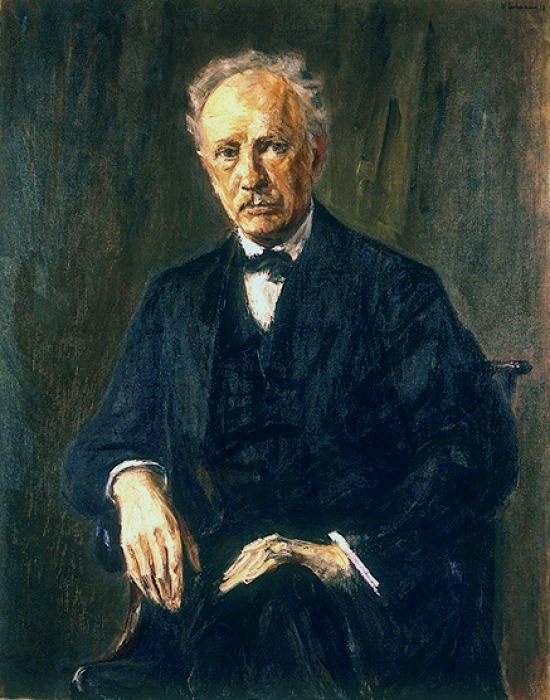

Richard Strauss

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth century, Richard Strauss became a very popular topic of conversation in Europe. His operas, Salome (1905) and Elektra (1909), provoked both discussion and scandal as his work seemed too progressive for his audiences. As a result, his musically challenging operas received negative critical response.

Strauss was born in 1864 in the German state of Bayern, the first child of Franz and Josephine Strauss. His father was a skilled musician and consequently a great influence on his musical development. At the age of four and a half Richard began playing the piano and violin, and at the age of six he began to compose his first pieces. His first compositions were heavily influenced by his father's musical preferences: Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven.

Perelman Theater

Dates are Mar. 2016.

| Wed, Mar 2 | 7:30 p.m. |

| Fri, Mar 4 | 8:00 p.m. |

| Sun, Mar 6 | 2:30 p.m. |

Approx. 2 hrs 30 min

No intermission

Although Franz's conservative outlook tried to steer his son toward academia first, Richard's schooling lasted only a short time. In 1884, Strauss' musical career began when Hans von Buelow, the director of the Meininger Hofkapelle, appointed the 23-year old assistant as conductor of his orchestra, one of the finest European orchestras at the time. This appointment proved to be the first and most important step for Strauss as a conductor and composer. Influenced by Alexander Ratter, a violinist of the Meininger orchestra, and freed from the musical taste of his father, Strauss started to compose "modern" music.

Early Compositions

From the start, Strauss' compositions divided audiences, but he felt that such reactions were an indication that he was doing something right. Instead of hindering his work he felt complimented, his innovative style a mark of the musical genius misunderstood by society.

As his reputation preceded him, Strauss became a director of the Munich Orchestra in 1886. Here he continued the concept of transferring literary pieces into musical form through the genre of the 'tone poem.' In the midst of his aspiring career, Strauss married the soprano singer Pauline d'Ahna in 1894.

Richard directed several of the great European orchestras, spending a few years with the Weimar Hofkapelle, the King's Opera in Berlin, and the Vienna Opera in Austria. During this period Strauss began composing operas and had his first work, Guntram, open in 1894.

Courting Controversy

In 1903 he saw Oscar Wilde's play, Salome, and was so fascinated that after the performance he went straight home to begin composing music for the opera. Two years later, Strauss' Salome opened in Dresden and shocked audiences. As a result of its controversial content, many European opera companies refused to perform Salome for fear of censorship. Strauss felt that in order to drive the drama in a play like Salome, it was necessary to compose music that intensified both the actions and emotions of the characters. Strauss had succeeded in creating an innovative style of opera with unusual music. The vocalist and musicians were challenged to follow his difficult and at times atonal verses while the audience was challenged to appreciate it.

In 1904, he traveled to the United States where he conducted his music in many major concert halls. During this tour, he conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music on March 4th and 5th.

Strauss continued his musical originality with Elektra (1909) and later with Der Rosenkavalier (1911), both composed with noted writer Hugo von Hofmannstahl. These were the last important operas that Strauss composed and which challenged the musical world. In the following years Richard Strauss wrote operas like Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, and Intermezzo which did not enjoy nearly the same degree of success. Strauss, still working on his old formulas, did not notice that European music was moving in another direction.

Strauss and the Nazis

When the Nazi party came into power in the 1930s, Strauss was appointed president of the Reichmusikkammer, the government department responsible for regulating art and culture. He had never interested himself in politics because, in his experience, governments shifted like sand.

Strauss had worked in Germany before the unification, under the Kaiser's united German government, through the First World War, under the new Weimar Republic, and now was confronted by working under the fourth government of his life, the Nazis. Strauss thought that the Nazis were simply a new band in the long parade of governments whose time would soon pass. As a result of these experiences, he accepted the position because it enabled him to continue to compose and support his family.

Strauss seemed to be pro-Nazi when he stepped in to conduct a Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra concert when the Jewish conductor Bruno Walter was denied permission. He then donated his fee to the musicians. He was not an anti-Semite. His daughter-in-law was Jewish as were his grandchildren.

Soon after Hitler came to power in January of 1933, a law was issued that all German theaters could no longer perform any piece of music or staged drama in which non-Aryans performed or had any part in the production. As a result, Mendelssohn's music was banned. However, Strauss had already begun to work on a new opera with his Jewish librettist Stefan Zweig. The work on the opera Die schweigsame Frau continued despite the law. Zweig was unsure it would be heard. Strauss had to go to both Goebbels and Hitler to get permission for the opera to be performed.

In a letter to Zweig, that the Nazis opened, he wrote that he conducted the concert years earlier only for the sake of "the orchestra." This was not the answer the Nazis expected. It was obvious that he was not one of them. A few weeks later, when his and Zweig's opera was about to be premiered the Dresden Opera, he asked to see the stage bill. When he saw that Stefan Zweig's name was not on it, he threatened to leave the city unless his name was added. They did as he had requested but as a result, the manager of the opera house was fired from his post.

Soon the Nazis were at Strauss' door and he was told to resign his post as president of the Reichsmusikkammer because of his "poor health." Later, when he refused to allow the government to house armament workers in his villa, the government took it from him. It was the destruction of the opera houses and concert halls of Germany, the center of his reality, that caused him to realize the times. The total destruction of the centers of the performing arts left him deeply depressed.

After the war, he worked with the new occupation government and was given permission to go to Switzerland where he composed an Oboe concerto for an American soldier, John de Lance, who was the principal oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1948, he wrote his five last songs for orchestra and voice. He died in his sleep in 1949 at the age of eighty-five.

The Aurora Series is underwritten by the Wyncote Foundation.

This production is funded, in part, through support from the William Penn Foundation.

New Production

Produced by the Curtis Institute of Music and presented in association with Opera Philadelphia and the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.